Cyborg, The Interim Belt Era, & The Death Of Meritocracy

And just like that, another belt was born, and with it the potential for a new era in women’s combat sports. In light of recent history, this is no insignificant occurrence, but as is becoming the norm when the UFC make big announcements, the decision left many MMA pundits (rightfully) shaking their heads.

A recap is necessary to unpack why. Since purchasing Strikeforce in 2011/12, the UFC has consistently refused to create a female 145-pound division. Then it spent a year forcing the consensus featherweight queen Cristiane “Cyborg” Justino to fight meaningless, potentially life-threatening fights at 140 pounds in the naïve hope that she could one day get down to 135 pounds. Then, abruptly, the UFC acquiesced to the dictates of common sense and, lo and behold, a new featherweight division was born. Still with me?

The inaugural championship bout was announced last Tuesday as taking place on February 11, 2017, in the main event of the UFC 208 pay-per-view from Brooklyn, and the MMA world breathed a collective sigh of relief.

There’s just one tiny detail that has been less-than-cordially received: Cyborg won’t be fighting for the belt in February. Instead it will be Holly Holm, the #4 ranked bantamweight, best remembered as the woman who KO’d Ronda Rousey in front of 57,000 people at Etihad Stadium, facing off against the #11 Germaine de Randamie, a Strikeforce import who’s yet to make noise (or win against ranked competition) in the UFC.

Like many of the UFC’s recent decisions, the match-up appears to be driven by short-term financial and promotional objectives. The UFC 208 card needed a headliner – the event having already been moved from January due to a dearth of available main eventers – and when Cyborg said she needed until March 2017 to recover from her last fight (a destruction of Lina Lansberg in September 2016), the promotion decided to forge ahead without her.

In fact, in an interview a few days before the Holm-de Randamie announcement, UFC president Dana White even went as far as implying that Cyborg might not get to fight for the belt at all – directly calling into question her motivation for turning down the February contest.

That a sustained period of hospitalization due to serious dehydration and severe depression wasn’t enough to convince the UFC to wait a meager four weeks for the true 145-pound queen is disturbing enough (especially since Rousey automatically became the champion at 135 pounds when Strikeforce was absorbed). But White’s decision to publicly reprimand Cyborg for prioritizing her health above the promotion’s bottom line, which was jeopardized in the first place because of the UFC’s dogmatic refusal to let her fight at her natural weight, is reckless. Even more so in light of the UFC’s recent laudable efforts to mitigate risks associated with weight-cutting.

This style of alarmingly short-sited and commercially driven decision-making has become somewhat commonplace for the UFC in recent times, no doubt motivated by the $1.8 billion that owners WME IMG had to borrow to finance its purchase of the company earlier this year.

Notwithstanding the incredible success of the promotion’s most recent pay per view showing, UFC 206, it too was overshadowed by the promotion’s dubious decision to declare the featherweight contest between Max Holloway and Anthony Pettis an interim championship bout a mere two weeks before the event.

Like the inaugural women’s championship, the decision appeared to be motivated by the need to put a shiny gold belt on the event poster. The event had, of course, been jeopardized after the headlining rematch between light heavy weight champion Daniel Cormier and Anthony Johnson was cancelled due to Cormier’s injury. Incredibly, the organization’s first choice was even more baffling: creating an interim light heavy weight championship to be contested between Johnson and middleweight Gegard Mousasi (who hadn’t fought at light heavyweight in nearly 3 years), which was ultimately turned down by Johnson.

Preceding UFC 206 were UFC 200, where an interim featherweight belt was created to cater to Conor McGregor’s desire to rematch Nate Diaz at welterweight; and UFCs 197 and 189, where an interim light heavyweight championship and an interim featherweight belt were respectively created to compensate for the champions’ late-notice withdrawal due to injury.

There are obvious problems with this practice of creating belts out of thin air to be contested by less-than-deserving contenders.

The first is the irrefutable damage this does to the legitimacy of the championship belt, and the correlative impact this is having on the landscape of the MMA fan base. As Dave Meltzer pointed out, it was the proliferation of belts (and weight classes) in boxing that made championship fights meaningless in the modern age. In contrast, the comparative restraint of the UFC, which traditionally only had five weight divisions, earned them much more in the way of fan loyalty.

This loyalty is inevitably waving in an era where three (likely four) interim belts have been created in the past 12 months, and none due to a prolonged period of absence of the champion as was the conventional justification (for example, Carlos Condit vs. Nick Diaz due to GSP’s 18 months absence due to an ACL tear in 2011-12; or the string of injuries that kept Cruz out from 2011-14).

Moreover, as 2017 gets underway it seems clear that the promotion will continue to pursue mainstream fans who are more interested in the entertainment external to the cage to events that unfold inside it – which is a risky game depending on how long super-stars McGregors and Rouseys stick around for, and whether the UFC’s PR-machine can find (or manufacture) suitable replacements.

Another problem is whether this style of promotion is reconcilable with the rankings system, which should theoretically have a significant (if not determinative) influence on who is eligible for a title-shot. As I’ve argued elsewhere, longer-term matchmaking for championship fights has demonstrated an increasing disdain for no.1 contenders and threatens the UFC’s ability to retain some of its greatest talents.

The UFC’s contempt for rankings is perhaps best reflected in the decision to give Dan Henderson, ranked no #11, a title shot against champion Michael Bisping in October. However, this was preceded by equally problematic title fights such as Lawler-Condit at UFC 195 (Condit was 2-3 in his last five bouts at the time), Cormier vs. Gustafsson at UFC 192 (Gustafsson had been KO’d in his last fight and a more deserving contender in Ryan Bader, who was riding a 5-fight winning steak, was passed over) and Ronda Rousey’s last two contests against Bethe Correia at UFC 190 and Holly Holm at UFC 193 (at the time these fighters were announced, neither Holm nor Correia were in the top-5 and hadn’t fought against ranked competition).

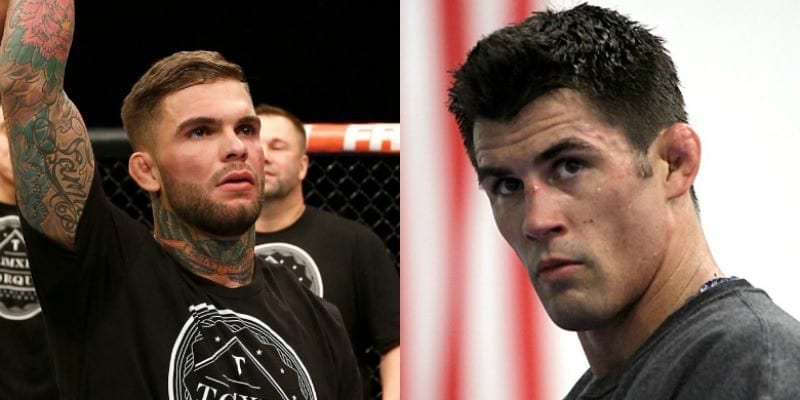

The upcoming co-main event of UFC 207, pitting bantamweight champion Dominick Cruz against #5 Cody Garbrandt, at the expense of the far more deserving challenger and no.1 contender TJ Dillashaw, who lost his belt to “the Dominator” in a razor close split decision in January, is just as troubling.

This style of money-driven decision-making has recently led top contenders such as Khabib Nurmagomedov (#1 at lightweight) and Julianna Pena (#3 at women’s bantamweight) to threaten to leave the UFC, and given the recent success of Bellator in picking up high profile fighters, it is entirely possible it will cost the promotion its monopoly on talent.

Given the way the UFC has treated many fighters, the creation of some competition with Bellator isn’t necessarily a bad thing. But an equally desirable outcome would be for the UFC’s new owners to re-visit what made the company so successful to begin with: a commitment to meritocratic match-making and a determination to learn from boxing’s mistakes.

With the recent formation of the Mixed Martial Arts Athletes Association, other efforts towards unionization picking up steam, and the US Congress showing interest in greater federal regulation of the sport (most notably by extending the Ali Act to MMA, so that title fights would have to be based on an objective ranking system), changes addressing many of these issues are perhaps inevitable.

The only question left is how long the UFC wants to resist the tide, and what kind of sport we’ll have left when it’s all said and done.